Articles

No Comments

By Voices

On 15, Dec 2014 | No Comments | In Community Activity | By Voices

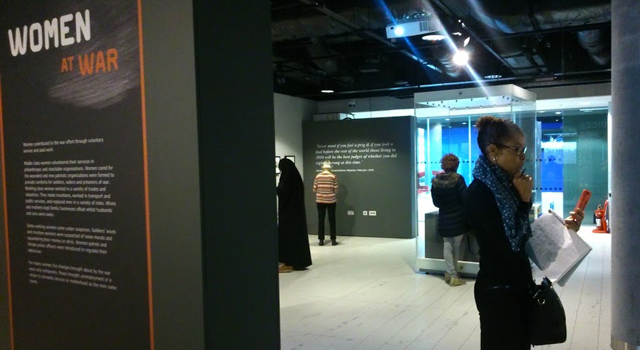

Workshops: Voices of the First World War: creative writing, conflict and reconciliation

11 October 2014, Library of Birmingham

Local writer Fiona Joseph and poets Garrie Fletcher and Antony Owen led creative writing workshops which used archive material about the First World War to inspire the writing. The event was held in partnership with Writing West Midlands and the Birmingham Literature Festival.

In both of the workshops the participants were able to use archive material held by Birmingham Archives, Heritage & Photography, which was on display in the Library of Birmingham’s exhibition Voices of War. Each of the practitioners was then able to work with the participants to produce poetry, short stories and letters that were inspired by the stories they had been able to explore.

Pieces of creative writing:

Sharon Hosker’s piece was created during Garrie and Antony’s session. The Watchmaker was inspired by the letters of those imprisoned from not wanting to fight. Vice Versa was inspired by the many women who worked at BSA during the First World War.

![[Library of Birmingham: MS 4669/2]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/ms-4669-2-300.jpg) The Watchmaker

The Watchmaker

by Sharon Hosker

I’m a skilled watchmaker

Perhaps there is no need for my trade at present

So I have time on my hands, lots of time, to waste

My toilet schedules are timed to perfection

Once at eight then again at four

With nothing in between

My meagre rations are served precisely

At seven, twelve and six

With nothing in between

Lights out at eight and no bright mornings

Fine in the summer, until winter evenings

Shut in a cell behind a curtain so dark

I don’t know if my eyes are open or closed

Time ticks by

Day after day

Relentless

Nothing changes

Just the sunrise

Or sunset

I’m a skilled watchmaker

Perhaps there is no need for my trade at present

I have two arms and two legs

Am fairly strong, can walk and talk

My enquiring mind picks things up

But I am

Condemned to this routine

Called life

I could labour on a farm, work in a factory

Join the fire brigade, dig holes

Repair homes, drive a truck

Just be of some use

The censored letters from my mother

Tell me my country is still at war

I am prepared to serve my country

Contribute something useful

My beliefs have imprisoned me

To waste my time for over a year

I won’t fight, I won’t kill

I could do so much to help

If only they would listen

My girlfriend wrote in September

‘I can’t love a feller what hasn’t died for his country’

I expect she’s my ex girlfriend now

Shells rushing like sea

Crash in waves

Over broken shores of mud

Bombs impregnated

With salty sweat

And fingerprints

Anonymous ammunition carried

Ever so gently

From weeping machines

Alongside babies

Struggling to feed

Men commanded to fight

By distant authority

Dying to survive

Women have no voice

No choice

But to make

Orphans

And widows

Of our German sisters

Vice Versa

Stephanie Neville’s piece was also created during Garrie and Antony’s session. The poem was inspired by the front cover of the Patriotic Song, Britannia’s Glorious Flag. As Stephanie said, ‘When I looked at it, my eye was immediately drawn to the top corner where there were some musical notes showing this was a piece of music written in a flat key, not what you would usually choose for an upbeat piece of music. Coupled with the stories of those who took a courageously anti-war stance, I wondered whether this could have been a tiny act of resistance, or at least a recognition that all was not joyful and triumphant. More normal for this kind of music would be a major key which lends itself nicely to a play on a double meaning. The other thing that struck me about the propaganda items, including this one, is how we look at them and smile at the naivety in which people were taken in by them. We recognise them for what they are … but somehow cannot apply that same good sense to current military propaganda, and so 100 years on we fall for the same myths, just dressed up in different language and imagery. Hopefully some, or all of that is portrayed in the attached poem’.

![Britannia's Glorious Flag [Library of Birmingham: Music / Song Sheets]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/music-songsheets-britannia.jpg) A (Mainly) Patriotic Song

A (Mainly) Patriotic Song

by Stephanie Neville

Mouths yawning wide

Eyes closed

We sing

Of patriotic duty

And naive hopes of victory

For flag and mother country

But

From somewhere in their midst

This one foresaw

There was a sombre note

And shared his voice

In this the choice

Of a B flat key

Unlocking

Some semblance

Of creativity

Perhaps he saw in his mind’s eye

On these dark lines

Which never meet

Too many

Sharps

Already

Cutting deep in flesh

And painted red

Perhaps he had already heard

What staccato beats

reverberate

Through shattered minds

And resonate

In yearning hearts

Frozen

In a silent fear

That dares no longer sing

And this his song

His only way

To say

He would not dance to the Major’s key

As looking back

With eyes made wise

With knowing smiles

We sagely nod

To this the tune

We say

We would not tap our feet to

And yet

The orchestra plays on

As still we listen

And close our eyes

To the murmur of these lullabies

A gentle drone

We hear as truth

As one white poppy

Still flutters

Unnoticed

In a sprawling sea of red

Kathleen Dixon Donnelly (www.suchfriends.wordpress.com), Jo Toye and Gemma Birch all attended Fiona Joseph’s workshop and were inspired by the exhibition to create the following pieces of work

Voices of War and Peace: The Great War and its legacy

1916

by Kathleen Dixon Donnelly

March 1916: London

Essayist and pacifist Lytton Strachey, soon to turn 36, is called before the Hampstead Tribunal to apply for status as a conscientious objector. He brings a cushion for his tush, explaining to the military men sitting in judgment on him, ‘I am a martyr to the piles…’

When they ask him, ‘If you were to find a German soldier raping your sister, what would you do?,’ Lytton answers, ‘I would try to interpose my own body between them.’

He then gives an impassioned explanation of his stand against the current war, reminding them, ‘I am the society you’re fighting for.’

October 1916: East Sussex

Painter Vanessa Bell, 37, is desperate. She is trying to find any way to keep her lover—Lytton’s cousin and former lover—painter Duncan Grant, just turned 31, out of the war.

The only way for a single man to avoid conscription is to work in service to his country. As a last resort, she finds a local farm, Charleston, which she can rent and live in with her sons. Duncan and their other painter/writer/intellectual/homosexual friends can then ‘work’ the farm.

Oh, and her husband, art critic Clive Bell, 34. He can help, too.

February 1916: Birmingham

‘Never mind if you feel a prig or if you look a fool before the rest of the world. Those living in 2016 will be the best judges of whether you did right or wrong at this time.’

–Gerald Lloyd, 30, conscientious objector

And we will…

THE HOME FRONT/WOMEN ‘The Telegram’

by Jo Toye

Boots. That’s what I remember – the sound of his boots up the entry.

Not that it was an unusual sound – when you live in a court of eight houses, eleven families, there’s a lot of comings and goings. But it was always quieter on Sundays, especially this early, before the kids were out playing hopscotch or throwing sticks to bring down the icicles from the guttering; before the door of the privy started going, or the few who weren’t drunk or asleep after a hard week’s work went off to chapel. That’s what I was doing, pinning my hair up for chapel, but I stopped with it half hanging down because I knew what those boots meant.

Slowly I took the pins from my mouth. The boots turned into the yard and crossed the cobbles. One, two, three paces… I held my breath. Four, five…Then a rap on the door. I closed my eyes and felt myself sway against the washstand. The knocker was raised and rapped again. I heard feet on stairs, the door tugged open… and then the cry. The cry of my neighbour, Bessie, as she saw the telegraph boy, and his sad eyes, and the envelope with the black cross he was holding out to her.

Not for me. Not this time.

I felt a sudden stinging. When I looked down and uncurled my fingers, I had driven the hairpins right into the palm of my hand.

My Darling Rose

by Gemma Birch

My Darling Rose

A week has passed since I wrote you last although, to my mind, it seems much longer. I received yours of the 8th three days ago but was sent as reserve to the front line shortly after and have only just returned to barracks. I should tell you we have had it a bit rough these last few days – a terrible storm hit on Thursday night which was positively beastly. The lightning lit the night sky, making it clear as day, and the Boche took full advantage. I shan’t say anymore lest I give you cause to worry, just know that I am going on alright. We all have to do our bit.

Just a quick note about your letter. I was most pleased to hear you are keeping well, it bucks me up to know you are not letting this dreadful war get you down. I was most surprised to receive another parcel from you so soon but the contents were gratefully received. The toffees and cigarettes I shared with Wilf – they seemed to raise his spirits while he awaits news of Lottie and the baby. And I must say I had a chuckle to myself when I unwrapped the scarf – I have doubtless been complaining about the weather too much! But it has served its purpose well and on these damp, cold days and freezing nights you, my dear, will be keeping me warm. Your new photograph stands proudly on the shelf next to my bunk, keeping watch over me while I sleep. I will be sure and kiss you goodnight every night I am here, my love.

Please reassure Mother that I received her letter, along with one from Joe and two from Alice. I will reply to them soonest.

Finally, my darling, I must send you the warmest of birthday wishes and many happy returns. Do not worry that I am losing my mind, I am well aware your birthday is still two weeks away, but I cannot be sure when you will receive this letter and I am now less than hopeful that this war will be over and I home in time to celebrate with you. I can scarcely believe that this is the first time since we were fifteen years old that we will be spending your special day apart, and in such circumstances too. But it only makes me more determined to do my part in ensuring this war is over sooner rather than later. I would ask one small favour of you though. On your birthday would you be kind enough to wear that dress you wore the night we first stepped out together? It will do me no end of good to be able to close my eyes and picture you as you looked that night. It will be enough to make me believe I am with you once again.

Well my girl, I know you will think me a sentimental old fool but it is these thoughts of you and of home that keep my spirits up. Each day is the same here – they all dawn grey and gloomy, but I am always glad that they do dawn as each one of them brings this war closer to its end which brings me another step closer to you.

But for now, my love, I will have to say goodnight.

Your ever loving Art.

![Munitions Workers [Library of Birmingham: WK/B11/6700]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/wk-b11-6700.jpg)

Submit a Comment