Articles

3 Comments

By Voices

On 10, Feb 2016 | 3 Comments | In Cities | By Voices

Refugee Relief during the First World War

Belgian Refugees in Birmingham (1914-1919)

Jolien De Vuyst, Ghent University

‘Black is typical of the terrible days through which our country is passing, and the depth of sorrow into which we have been plunged; red, is the blood that has been shed; but golden is the kindness of the British people, and never can the Belgians forget the generosity and warmth of their reception’. Belgian refugee priest, referring to the colours of the Belgian flag. (War Refugees’ Committee, 1914)

The First World War can be identified as a ‘total war’, since it affected every level of society, far beyond the front and the battles. The industrialized warfare caused disastrous situations that were never seen before. Massacres, arson, rape, pillaging and deportations were common. Next to this, the ‘Great War’ brought on famine, epidemics and a worldwide stream of refugees (Cabanes, 2014). In this respect, the twentieth century often has been called the ‘century of the refugee’ (Myers, 2001). In spite of all the destruction, the atrocities unleashed a worldwide explosion of humanitarian help. The First World War, thus, can also be seen as a watershed in the redefinition of humanitarianism and consequently social work. The war was determinative of changing the discourse from ‘charity’ to ‘human rights’ and was a catalyst for the transition of charity towards a more professional and institutionalized social work. Since the problems caused by the First World War were of a global nature, they required an international and transnational approach. This resulted in an inter- and transnationalization of, amongst other things, humanitarianism, and it also marked a decisive turning point in which the initial outlines of the current (inter)national policies regarding refugees and human rights were drawn (Cabanes, 2014; Little, 2014). The professionalization of relief, in connection to the First World War, is still underexplored in research. This study wants to focus on the war from a social work perspective, more particularly on the specific case of the Belgian refugee relief in Birmingham, as “humanitarian intervention arguably demonstrated its greatest power at the local level” (Little, 2014, p. 7).

![Belgians in Birmingham, Birmingham Gazette, 16 October 1914 [Birmingham Archives and Heritage Service]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/belgian-refugees-gazette.jpg) As mentioned before, the unprecedented violence against civilians and its concurrent problems induced a worldwide stream of refugees. It is estimated that four million people, originating from the Western Front, sought exile in another country. One and a half million of them were Belgians, who felt forced by the German violence to leave home and country behind (Marrus, 1985; Kushner & Knox, 1999; Purseigle, 2007). One million Belgians fled to the Netherlands, 250.000 to France and another 250.000 to England, it still being the largest refugee movement in British history (Tallier, 1998; Kushner & Knox, 1999). The brutal invasion of Belgium was reported in newspapers worldwide and caused indignation in Allied and neutral countries. Thereby, Belgium became the symbol of a heroic country (Cahalan, 1982; De Schaepdrijver, 2010). Lady Lugard (1915), initiator of the War Refugees’ Committee in London, wrote in this account: “Belgium bore for a time the burden of the world, and the world can never forget and never repay” (p. 429). Accordingly, the British people saw refugee relief as their duty (Cahalan, 1982; Purseigle, 2007). The mass influx of Belgian refugees in England caused a great expansion of voluntary effort. It is believed that this was the largest relief operation ever seen in British history: there were over 2.000 official relief committees, and more than 100.000 people of all classes offered hospitality (Kushner, 1999; Myers, 2001; Fowler & Gregson, 2005; Grant, 2012). Upon arrival in England, the majority of the Belgian refugees were sent to ‘reception camps’ in London. The main camps were Alexandra Palace and Earl’s Court, and functioned as dispersal centres. They took care of the refugees before they were allocated to permanent housing all over the country (Ministry of Health, 1920; Myers, 2001; Storr, 2002).

As mentioned before, the unprecedented violence against civilians and its concurrent problems induced a worldwide stream of refugees. It is estimated that four million people, originating from the Western Front, sought exile in another country. One and a half million of them were Belgians, who felt forced by the German violence to leave home and country behind (Marrus, 1985; Kushner & Knox, 1999; Purseigle, 2007). One million Belgians fled to the Netherlands, 250.000 to France and another 250.000 to England, it still being the largest refugee movement in British history (Tallier, 1998; Kushner & Knox, 1999). The brutal invasion of Belgium was reported in newspapers worldwide and caused indignation in Allied and neutral countries. Thereby, Belgium became the symbol of a heroic country (Cahalan, 1982; De Schaepdrijver, 2010). Lady Lugard (1915), initiator of the War Refugees’ Committee in London, wrote in this account: “Belgium bore for a time the burden of the world, and the world can never forget and never repay” (p. 429). Accordingly, the British people saw refugee relief as their duty (Cahalan, 1982; Purseigle, 2007). The mass influx of Belgian refugees in England caused a great expansion of voluntary effort. It is believed that this was the largest relief operation ever seen in British history: there were over 2.000 official relief committees, and more than 100.000 people of all classes offered hospitality (Kushner, 1999; Myers, 2001; Fowler & Gregson, 2005; Grant, 2012). Upon arrival in England, the majority of the Belgian refugees were sent to ‘reception camps’ in London. The main camps were Alexandra Palace and Earl’s Court, and functioned as dispersal centres. They took care of the refugees before they were allocated to permanent housing all over the country (Ministry of Health, 1920; Myers, 2001; Storr, 2002).

In Birmingham, a local War Refugees’ Committee (WRC) was established under the chairmanship of Elizabeth Cadbury, in order to coordinate and answer the needs of the Belgian refugees. As early as the fourth of September 1914, the first fifty refugees arrived. In Britain, the refugees were almost an ‘attraction’: British people visited them or welcomed them at train stations upon arrival (Cahalan, 1982; Verleyen & Demeyer, 2013). This was also the case in Birmingham, when the first refugees arrived at New Street Station.

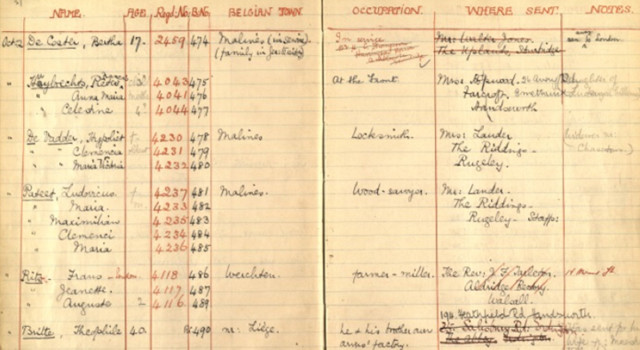

![Belgian Refugee Register, War Refugees’ Fund (Birmingham and District), 1914-1919 [Birmingham Archives and Heritage Service: MS652/6]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/war-comm-mins.jpg) Elizabeth Cadbury wrote: “[there was] tremendous excitement in New Street, as word got round that the first Belgians were arriving, and they finally departed to Uffculme in a char-a-banc amidst great cheers” (as cited in Roberts, 2014, p. 32). In total, approximately 5.000 Belgian refugees would be allocated to Birmingham. Their records are well registered and kept in the ‘Belgian Refugee Register’ at the Birmingham Archives and Heritage Services, together with the Minute Books of the WRC (Birmingham Archives and Heritage Services, “War Refugees Fund (Birmingham and District)”, MS652). The WRC took responsibility to help the refugees with, amongst other things housing, employment, education and entertainment. Several subcommittees were founded to deal with these matters. Concretely, refugees were (re-)allocated, the committee organised English lessons for adults, founded a ‘Belgian School’, raised funds to maintain destitute Belgian families, helped families to be self-supportive, provided opportunities for employment, etc. They also established a Lost Relatives Bureau, a Belgian club (Le Cercle Belge) and a maternity home. Material help was also offered by the distribution of donated clothing, boots and other gifts (War Refugee Committee, 1915; Roberts, 2014; Van Gorp, 2014).

Elizabeth Cadbury wrote: “[there was] tremendous excitement in New Street, as word got round that the first Belgians were arriving, and they finally departed to Uffculme in a char-a-banc amidst great cheers” (as cited in Roberts, 2014, p. 32). In total, approximately 5.000 Belgian refugees would be allocated to Birmingham. Their records are well registered and kept in the ‘Belgian Refugee Register’ at the Birmingham Archives and Heritage Services, together with the Minute Books of the WRC (Birmingham Archives and Heritage Services, “War Refugees Fund (Birmingham and District)”, MS652). The WRC took responsibility to help the refugees with, amongst other things housing, employment, education and entertainment. Several subcommittees were founded to deal with these matters. Concretely, refugees were (re-)allocated, the committee organised English lessons for adults, founded a ‘Belgian School’, raised funds to maintain destitute Belgian families, helped families to be self-supportive, provided opportunities for employment, etc. They also established a Lost Relatives Bureau, a Belgian club (Le Cercle Belge) and a maternity home. Material help was also offered by the distribution of donated clothing, boots and other gifts (War Refugee Committee, 1915; Roberts, 2014; Van Gorp, 2014).

Members of the Birmingham War Refugees’ Committee were deliberately chosen from different religious and political groups (Roberts, 2014). This committee was compound of, amongst others, Quakers (different members of the Cadbury family and the Sturge family), Catholics (Edward Ilsley, Archbishop of Birmingham, and Mr. & Mrs. Ratcliff), Methodists (Rev. Pinchard) and Unionists (Mrs. Kenrick and Mrs. Nettlefold) (Minute books of the Allocation Committee of the War Refugee Committee). Their (personal) influence on the Birmingham WRC and other local organisations still has to be studied in closer detail. This is also the case for the underlying networks supporting the WRC.

![Belgian refugees at Moor Green House, Moseley, Birmingham, L. Lloyd, 1914 [Photograph]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/belgian-refugees-photo.jpg) The experience of working with Belgian refugees certainly has had an impact on several British civilians. As Kushner (1999) wrote: “In the British case, many of those involved in refugee work in the inter-war period and beyond had their first experiences working with or on behalf of the Belgians” (p. 5). So it can be said that the Belgian exile influenced relief workers and gave an impulse to refugee relief work. This impulse and increase in relief work was also reflected in the demand for educated social workers. For the first time the demand exceeded the supply, making way for new opportunities (Macadam, 1925). The Great War was a stimulus to the professionalization of an independent social work, and “the voluntary worker [was] rapidly becoming extinct” (Macadam, 1925, p. 168). In 1908, the University of Birmingham was the first university in the United Kingdom to give future social workers the full status as students. They organized a one year social studies course. The war made way for new possibilities, and they anticipated on the wartime needs by the foundation of a short emergency course as ‘Welfare Supervisors’ in munitions factories and the new option to spread the social studies course over two years. That way students could combine their wartime tasks with their studies (Davis, 2008). In other words, the social work profession as well as social work education was given a boost.

The experience of working with Belgian refugees certainly has had an impact on several British civilians. As Kushner (1999) wrote: “In the British case, many of those involved in refugee work in the inter-war period and beyond had their first experiences working with or on behalf of the Belgians” (p. 5). So it can be said that the Belgian exile influenced relief workers and gave an impulse to refugee relief work. This impulse and increase in relief work was also reflected in the demand for educated social workers. For the first time the demand exceeded the supply, making way for new opportunities (Macadam, 1925). The Great War was a stimulus to the professionalization of an independent social work, and “the voluntary worker [was] rapidly becoming extinct” (Macadam, 1925, p. 168). In 1908, the University of Birmingham was the first university in the United Kingdom to give future social workers the full status as students. They organized a one year social studies course. The war made way for new possibilities, and they anticipated on the wartime needs by the foundation of a short emergency course as ‘Welfare Supervisors’ in munitions factories and the new option to spread the social studies course over two years. That way students could combine their wartime tasks with their studies (Davis, 2008). In other words, the social work profession as well as social work education was given a boost.

As mentioned before, the professionalization of relief still has to be explored into detail. This blog is an introduction to how the Belgian exile during the First World War may have challenged and influenced social work. But it is also important to research the underlying networks of refugee relief, as well as the post-war effects on the further development of social work. 1918 was not the end of humanitarian and social work related to the war, as most refugees weren’t able to return until 1919 or 1920, and countries were still preoccupied with reconstruction.

References:

Cabanes, B. (2014). The Great War and the origins of Humanitarianism, 1918-1924. New York (N.Y.): Cambridge university press.

Cahalan, P. (1982). Belgian refugee relief in England during the Great War. New York/London: Garland.

Davis, A. (2008, November). Celebrating 100 years of Social Work. Retrieved from http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-social-sciences/social-policy/IASS/100-years-of-social-work.pdf

De Schaepdrijver, S. (2010). Belgium. In: J. Horne (ed.). A companion to World War I (pp.188-201). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Fowler, S & Gregson, K. (2005, May). ‘Bloody Belgians!’. Ancestors, 33, 43-49.

Grant, P. R. (2012). Mobilizing charity: non-uniformed voluntary action during the First World War (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London, England). Retrieved from http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/2075/

Kushner, T. (1999). Local heroes: Belgian refugees in Britain during the first world war. Immigrants & Minorities: Historical Studies in Ethnicity, Migration and Diaspora, 18(1), 1-28.

Kushner, T., & Knox, K. (1999). Refugees in an age of genocide : global, national and local perspectives during the twentieth century. London: Cass.

Little, B. (2014). An explosion of new endeavours: Global humanitarian responses to industrialized warfare in the First World War era. First World War Studies, 5(1), 1-16.

Lugard, F.L. (1915, March 26). The Work of the War Refugees’ Committee. Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 63(3253), 429-440.

Macadam, E. (1925). The equipment of the social worker. New York: Holt.

Marrus, M. R. (1985). The unwanted : European refugees in the twentieth century. New York (N.Y.): Oxford university press.

Ministry of Health. (1920). Report on the Work Undertaken by the British Government in the Reception and Care of the Belgian Refugees. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Myers, K. (2001). The hidden history of refugee schooling in Britain: The case of the Belgians, 1914-18. History of Education, 30(2), 153-162.

Purseigle, P. (2007). ‘A Wave on to Our Shores’: The exile and resettlement of refugees from the western front, 1914-1918. Contemporary European History, 16(4), 427-444.

Roberts, S. (2014). Birmingham: Remembering 1914-18. Stroud: The History Press.

Storr, K. (2002, June). Belgian Refugee Relief: an example of ‘Caring Power’ in the Great War. Women’s History Magazine, 41, 16-19.

Tallier, P-A. (1996). Les réfugiés belges à l’ètranger durant la Première Guerre Mondiale. In: A. Morelli (ed.). Les émigrants belges: Refugiés de guerre, émigrés économiques, réfugiés et émigrés politiques ayant quitté nos regions du XVIème siècle à nos jours (pp. 17-42). Brussels: EVO.

Van Gorp, A. (2014). “Weary and worn in mind and body”: Belgian refugees in Birmingham, 1914-1919. Paper presented at ISCHE 36, London.

Verleyen, M., & Demeyer, M. (2013). Augustus 1914 : België op de vlucht. Antwerpen: Manteau.

War Refugee Committee (Birmingham District). (1914, October). War Refugee Committee Report. Birmingham: Cornish Brothers Ltd.

War Refugee Committee (1915). War Refugee Committee Report (Birmingham Branch). Birmingham: Birmingham Printers Ltd.

Images

Belgians in Birmingham, Birmingham Gazette, 16 October 1914 [Birmingham Archives and Heritage Service]

Belgian Refugee Register, War Refugees’ Fund (Birmingham and District), 1914-1919 [Birmingham Archives and Heritage Service: MS652/6]

Belgian refugees at Moor Green House, Moseley, Birmingham, L. Lloyd, 1914 [Photograph]

-

I am trying to discover more about some Belgian Woodcarvers who took refuge in Lincolnshire 1914/15 and did some beautiful carving in our churches

-

Hi Jane,

Have a look at our database, you might find something there. I know that we have several Lincolnshire entries: https://belgianrefugees.leeds.ac.uk/database/

-

-

Dear people,

My grandparents came with my mother As a child to Leeds as Refugees during the 1st World War.

My mum wrote her life story which I am now translating into English. She writes about her time in Leeds. Her parents Jozef Armand Peeters (dob 19 March 1890 and Stephania Van

doren (dob 8th July 1892) both born in Mechelen, Belgium.

My mother`s name Rosalie Peeters (dob 28 november 1911).

I am not exactly sure what year they fled to Britain. My grandparents worked in the Vickers factory in Leeds. They also brought Jozef`s father.

I will send some more information oncde I have traslated my mum`s diary.Could you find some info or their registrations ? I think they came on a boat from Antwerp also!It would be wonderful to find out some more detail and I could exchange my mother`s memory as a child in Leeds. She stayed in contact with people she had met there all her life!Thank you!

Submit a Comment

Comments