Articles

No Comments

By Voices

On 07, Aug 2018 | No Comments | In Cities | By Voices

Improvements in Welfare of the Blind

Niall Herbert, University of Worcester

Improvements to welfare and support of the blind in Britain were accelerated by the First World War and the number of servicemen blinded by gas attacks.

The system of welfare for the blind was in need of drastic reform prior to the First World War. Charities, that had traditionally provided employment, care and assistance were failing in the face to meet growing demand, with insufficient financial resources leaving those unable to obtain charity suffering. In February 1914, Labour MP Phillip Snowden pointed out there were ‘5,000 blind people in the workhouses, 5,000 in receipt of parish relief, 7,000 begging [for] their bread in the streets’. He pleaded for a ‘scheme of national assistance which will remove these people from having to accept pauper relief or beg for their bread’. A month later, Labour MP George Wardle, supported by the National League for the Blind (NLB), argued in the House of Commons that blind citizens should be ‘made self-supporting, and the incapable and infirm maintained in a proper and humane manner’. In response, the government established a three-year committee to evaluate the concerns raised.

The outbreak of war disrupted the momentum of the Blind Welfare campaign but the committee’s 1917 findings were conclusive. There was a failing of education and lack of blind schools, with blind children academically two years behind other children. There were 3,000 blind people unemployed, many facing employment discrimination. The committee also noted that many blind people were frustrated with the limited employment opportunities provided by voluntary charities in trades, such as brush and basket making. The committee suggested that more secondary schools and specialist workshops should be built, and that the government should subsidise blind citizens’ wages to eliminate employment discrimination. Many improvements would however have to wait until post-war era.

German gas attacks on the Western Front in summer of 1915, resulted in British servicemen being temporarily, or even permanently blinded. By September the government reported ‘1,381 cases of injury to eyesight, many of them blind’. By July 1917, 20,013 British soldiers had suffered permanent or temporary blindness. These years constituted the peak of British causalities from gas, some servicemen were treated in the frontline hospitals; others who were permanently blinded were sent back to hospitals in Britain. Arthur Pearson, a blind philanthropist and president of the NLB, convinced many blinded servicemen to attend St Dunstan’s newly formed in 1915, at Regent’s Park, which provided free rehabilitation and treatment. During the course of the First World War 1,833 British servicemen were permanently blinded and 95% of them, at some stage, spent time at the charity helping them adapt to live after blindness, making St Dunstan’s a vital charity for the rehabilitation of blinded servicemen.

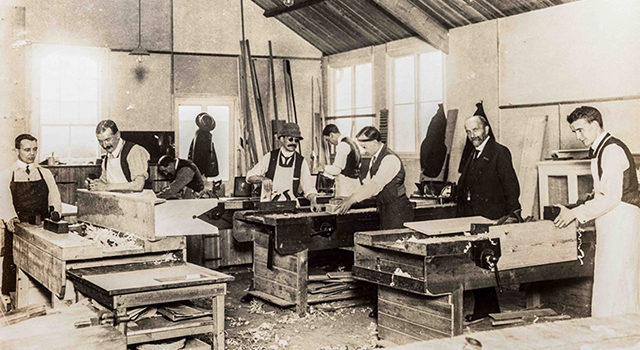

Pearson’s primary goal was for blinded servicemen ‘to be led to look upon blindness, not as an affliction, but as a handicap; not merely as a calamity, but as an opportunity’. He added: ‘we do not want the men who have given their sight for us to be hampered by difficulties that forethought ease remove from their way.’ Blinded servicemen were taught Braille by specialist teachers and learned new trades: poultry farming, type writing, mat making, piano tuning, massaging, boot making, joinery, telephony and basket making, skills and occupations, which would help provide future employment and a greater sense of independence. While training blinded servicemen were paid five shillings a week. The speed in which blinded servicemen learned new trades was impressive, English Journalist Sidney Dark wrote on a visit to St Dustan’s in 1915 that ‘at St Dunstan’s men learned in six to nine months what it took four to five years to teach blind men in other institutions’. Pearson, when speaking upon the training opportunities that St Dunstan’s was offering blinded servicemen, commented in April 1916: ‘the least we can do is to take every means in our power to ensure that [they] are placed in a position successfully to flight their stern battle against so terrible a handicap as the loss of sight.’ After their period of training had concluded, men at St Dunstan’s returned home, only staying at the charity if they had nowhere else to go. However, assistance did not end after men left at the conclusion of their training courses, as blinded servicemen were given help finding jobs, while financial advice, loans and legal and medical advice were also made readily available by St Dunstan’s.

In April 1916, the Western Daily Press reported that 51 blinded servicemen had passed through St Dunstan’s learning a variety of trades; by August 1918, it was able to report over 500 blinded servicemen had set up their own businesses or found employment due to their training. Blinded servicemen who began their own poultry farming businesses with assistance from family relations were given three months free training by St Dunstan’s and many blinded servicemen became highly successful and valuable type writers and basket makers. Tommy Rogers, a blinded serviceman who became a teacher at St Dunstan’s, described his time at the organisation as: ‘the light [which] began to disperse the mist of frustration. Once again I was a useful member of society.’ Crucially, as The Rev. Lewis, who himself was blind, commented in January 1919: ‘The old-time blind man was generally beggar of the streets, but nowadays work [can] be found for men who [have] been trained.’ Yet, in 1919, Lewis’ comments related to blinded servicemen at St Dunstan’s, but not the whole blind population.

The morale of the staff and blinded servicemen at St Dunstan’s remained high during the First World War, Pearson felt justified in making the claim ‘that St Dunstan’s is one of the most cheerful places in the kingdom’. Similarly, Sidney Dark wrote in 1915: ‘the great army of men and women who helped Arthur Pearson in his work, the majority of them giving up their whole time without any payment whatever, were no more cheerful than the active, healthy, eager young blind men who were learning in an atmosphere of good-fellowship to start life again.’ Entertainment was provided for the servicemen almost every evening; furthermore, recreation and sport were seen as a key part of maintaining morale and physical fitness, while providing the men with a sense of freedom. Rowing, swimming, wresting, boxing, dancing, bike riding and sewing were all frequent organised activities. Blinded serviceman Walter James Moss reminisced ‘there was little, in fact, in the realm of sport that the dark prevented us from attempting.’ Pearson referring to rowing, remarked ‘to the blinded man there is joy in being out on the water, pleasure in the exercise, pleasure in handling the oars, pleasure in the sense of movement, pleasure in the sounds that are full of pictorial suggestion.’

The work of St Dunstan’s did not evade government attention; Hayes Fisher, the chairman of the governments committee investigating Blind Welfare from 1914-1917 stated: ‘Where we find a splendid institution like the one run at St. Dunstan’s … it is our duty to cast our eyes forward so that we may know that the provision for the blind is likely to be adequate for the future.’ The growing number of blinded servicemen and success of St Dunstan’s drew recognition to the government’s own failing system of care. Yet, although the government failed to provide sufficient care to blinded servicemen, public support for the charities caring for wounded servicemen increased dramatically during the First World War. A staggering 18,000 new charities were created during the conflict, which constituted to a 50 per cent rise from 1914. The number of men and women volunteering in charities also tripled from 400,000 to 1.2 million. In wartime, charitable giving was a key part of life on the home front and St Dunstan’s benefited from it. The peak of British casualties from gassing coincided with the largest income of charitable donations and endowments in metropolitan areas, suggesting an increase in popular support for the nations blinded servicemen. From 1916, many towns, villages and cities organised charity sport matches, bazaars, musical concerts and auctions to raise money for St Dunstan’s. The Marquees of Crewe believed that the increased fundraising came because ‘the Services and the nation are [now] in effect one’ as the responsibility for their care ‘rests upon all of us’.

St Dunstan’s took an active role in raising money, appealing for donations and collecting money. From 1916, the charity sold a number of postcards containing sorrowful messages that were accompanied with disheartening images of blinded servicemen on either the battlefield or home front, drawn by artists. On the back of each of the cards was text consisting of around 100 words describing the image and the work being done at St Dunstan’s. From 1916 to late 1917, three sets of five pictorial postcards, the first set containing five and the second and third containing six postcards, were printed in colour and sold at 6d. Alternatively, St Dunstan’s sold the postcards for one penny each Striking, while the captions on each of the postcards varied, the recurring underlying message of the cards was that blinded servicemen had been blinded as a result of fighting for their country; yet their future under the current welfare system looked bleak. As conservative MP Gerald Hohler described the situation of blinded servicemen in February 1916: ‘He is entirely incapable of work for his lifetime, yet he is a young man and is married … For any children born nine months after he comes back from the War there will be no support of any kind. They are practically paupers, and the small pension which he is to get will have to go to maintain these additional children.’ By the selling the postcards it helped St Dunstan’s generate funds, and allowed people purchasing them to feel they were doing their patriotic duty, contributing to wounded servicemen.

The Blind Welfare campaign had benefited from growing awareness and support given to blinded servicemen, which reached a new high with a public demonstration held at Trafalgar Square in July 1918. In the post-war era, donations to charities treating wounded servicemen remained high as did support for proposals to improve the welfare of the blind. The NLB demonstration at Hyde Park in August 1919 was one of the most noticeable protests in a year of public unrest in many towns and cities. When a bill to improve Blind Welfare failed to get a reading in the Commons in November 1919 demonstrations continued to take place. In March 1920, when the bill’s next reading met with only limited opposition, The Dundee Courier commented on the unwavering and unfaltering support noting that: ‘although the blind see no man, every man sees the blind’. The landmark legislation, the Blind Persons Act (BPA), finally became law in September 1920. The act ensured that the government took more responsibility towards the blind, through two important provisions: 1) an earlier and increased pension, 2) greater duty placed on local councils to promote the welfare and employment of the bling. Many local authorities delegated these duties to charities, like St Dunstan’s, and provided them with financial support. Through the BPA, local Charities had the means to provide improved support for the blind, whether they had been in the military or not. The Blind Welfare campaign benefitted from their association with the sacrifice of servicemen, which generated both support and government action.

All images courtesy of Blind Veterans UK.

![Fund-raising postcard [Image: Blind Veterans UK]](https://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/blind-veterans-uk-postcard2.jpg)

![Carpentry at St Dunstan’s [Image: Blind Veterans UK]](https://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/blind-veterans-uk-st-dunstans-carpentry.jpg)

![Blinded servicemen and staff in front of St Dunstan's [Image: Blind Veterans UK]](https://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/blind-veterans-uk-st-dunstans.jpg)

![Women collecting for St Dunstan’s [Image: Blind Veterans UK]](https://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/blind-veterans-uk-st-dunstans-collectors.jpg)

![Fund-raising postcard [Image: Blind Veterans UK]](https://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/blind-veterans-uk-postcard.jpg)

![Postcard of St Dunstan's [Image: Blind Veterans UK]](https://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/blind-veterans-uk-st-dunstans2.jpg)

Submit a Comment