Articles

One Comment

By Voices

On 18, May 2015 | One Comment | In Commemoration | By Voices

Connections between Great Wars; 1793-1815 and 1914-1919

Nick Mansfield, Senior Research Fellow in History, University of Central Lancashire

Britain has embarked on a massive public history jamboree to commemorate the centenary of the First World War. Its overwhelming storyline is emotive, which I suspect that the citizen soldiers who I knew as a boy, particularly those rural representatives that I Interviewed in the 1980s, would have found distasteful [1].

The generation-long French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, 1793 to 1815, with short breaks in 1802 and 1814, was often termed the ‘Great War’ in nineteenth century histories. Yet very little has appeared in the current centenary on the connections between the two huge world-wide conflicts, almost exactly a hundred years apart. Such connections were also absent from contemporary reporting between 1914 and 1918, perhaps because Britain’s old and traditional enemy was now its main ally. However some press reports, especially of the early fighting, point out that Flanders was not a new venue for the British army and mention the proximity of former battlefields like Roubaix and Waterloo and especially the site of Mons in 1914 being almost contiguous with Marlborough’s campaigning.

Some recent British social historians have made a powerful case that Britain’s mobilisation and the loss of life in this earlier ‘Great War’ at the turn of the nineteenth century was proportionately greater than in the First World War [2].

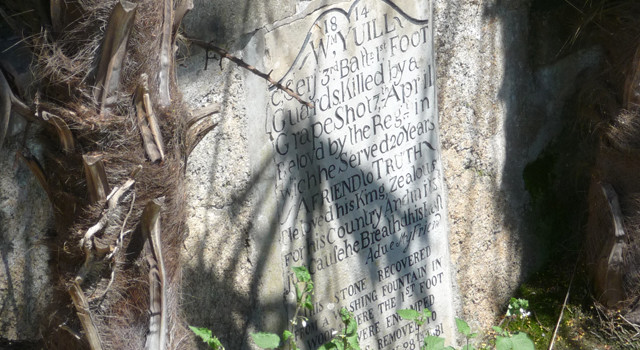

![Gravestone of William Yuill [Image courtesy of Nick Mansfield]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/cemiterio-william-yuilly.jpg) Yet in contrast to the early twentieth century conflict, relatively little evidence of national mourning or private grief is recorded in the widespread soldiers’ accounts, particularly the new phenomena of rank and file memoirs, which followed after 1815. With the long peace the deaths of senior officers might be recorded in cathedrals and the families of junior officers might erect monuments in parish churches. But the thousands of the rank and file fatalities received nothing but an unmarked grave, with often families receiving little word about their fates. Non-commissioned fatalities only began to be reported by name in 1799. There are a few exceptions to this trend; some graves of junior seamen, marines and soldiers killed in various operations in southern Spain, are found in the ‘Trafalgar’ Cemetery in Gibraltar and Sergeant William Yuill, is the solitary ranker in the Coldstream Cemetery outside Bayonne in south west France, unluckily killed the day after Napoleon had abdicated, an event unbeknownst to the protagonists.

Yet in contrast to the early twentieth century conflict, relatively little evidence of national mourning or private grief is recorded in the widespread soldiers’ accounts, particularly the new phenomena of rank and file memoirs, which followed after 1815. With the long peace the deaths of senior officers might be recorded in cathedrals and the families of junior officers might erect monuments in parish churches. But the thousands of the rank and file fatalities received nothing but an unmarked grave, with often families receiving little word about their fates. Non-commissioned fatalities only began to be reported by name in 1799. There are a few exceptions to this trend; some graves of junior seamen, marines and soldiers killed in various operations in southern Spain, are found in the ‘Trafalgar’ Cemetery in Gibraltar and Sergeant William Yuill, is the solitary ranker in the Coldstream Cemetery outside Bayonne in south west France, unluckily killed the day after Napoleon had abdicated, an event unbeknownst to the protagonists.

Yet whilst contemporary civilian mortality rates were high, there is no doubt that working class families grieved in 1815 in a largely unrecorded story. This is chronicled by a radical Scottish hatter, whose father was a soldier and who had been a boy during the conflict: ‘The French War was carrying desolation over a large portion of Europe, and there were few of the people even in the lonely, and sequestered valleys who had not occasion to mourn some dear relative who had fallen in the service of his country….and many a loving heart was left with an empty void which might never be filled.’ In addition, even the unmarked graves were not always respected. Communal grave-pits of the big battles were excavated within decades, to be ground up for bone fertiliser and imported to drive the British agricultural revolution. The ‘father of the fertiliser industry’ Justus von Liebig claimed: ‘Already in her eagerness she [England] has turned up the battlefields of Leipsic and Waterloo, and those of the Crimea.’ Such actions would have been unthinkable both post 1918 and especially in the context of the current centenary [3].

![Fred and Martha Mansfield [Image courtesy of Nick Mansfield]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/fred-and-martha-mansfield.jpg) However folk knowledge of momentous conflicts does persist down the years in working class families. My father Fred Mansfield (1912-2004), who spent his working life in the Cambridge building trade, told us approvingly that Oliver Cromwell had stabled his horses in the chapel of King’s College Chapel, and wasn’t that one in the eye for the class enemy; Cambridge University. The same boast: ‘Damn the monarchy, I want none; I wish to see all the churches pulled down and King’s Chapel made a stable of’, was made as a toast at a private dinner of radical artisans in Cambridge on 30th January 1793. The main dish – a calf’s head – was a deliberatively provocative revolutionary gesture, as celebratory of the anniversary of the execution of King Charles 1 in 1649. The toaster, a journeyman baker named John Cook, was lucky only to be imprisoned for sedition in the anti-Jacobin ‘White Terror’ conducted by the British government. This intensified by the outbreak of war with Revolutionary France on the very day following Cook’s drunken boast [4].

However folk knowledge of momentous conflicts does persist down the years in working class families. My father Fred Mansfield (1912-2004), who spent his working life in the Cambridge building trade, told us approvingly that Oliver Cromwell had stabled his horses in the chapel of King’s College Chapel, and wasn’t that one in the eye for the class enemy; Cambridge University. The same boast: ‘Damn the monarchy, I want none; I wish to see all the churches pulled down and King’s Chapel made a stable of’, was made as a toast at a private dinner of radical artisans in Cambridge on 30th January 1793. The main dish – a calf’s head – was a deliberatively provocative revolutionary gesture, as celebratory of the anniversary of the execution of King Charles 1 in 1649. The toaster, a journeyman baker named John Cook, was lucky only to be imprisoned for sedition in the anti-Jacobin ‘White Terror’ conducted by the British government. This intensified by the outbreak of war with Revolutionary France on the very day following Cook’s drunken boast [4].

The huge global forces beyond their control effected British working class communities in 1793, just as much as they did in 1914. As Linda Colley and others have reminded us, the mentality of the new working class of the early nineteenth century could also be patriotic and loyalist, as well as radical. Again a vestige of this potentially ‘multiple identity’ survived in my own family. My father’s grandmother, Martha Mansfield, nee Wayman (1860-1941) told him that her grandmother, as a little girl, walked from her village of Kingston into Cambridge to view the street bonfires celebrating a great victory. The occasion was recorded more officially: ‘On 7th of November [1805], there was a general illumination on account of the battle of Trafalgar. The bells of Great St. Mary’s rang a dumb peal for Lord Nelson.’ [5]. Family legend also remembers the name of Stephen Mansfield, who was said to have fought at Waterloo.

So perhaps the combatants of 1793-1815 are closer to living memory than one might think, and the continuities with the citizen armies of 1914-18 are more vivid. The relative ease with which British society, and especially the working class, engaged in twentieth century wars, may owe much to knowledge of military service in the earlier great conflicts.

Nick Mansfield, Senior Research Fellow in History, UCLan, member of the University of Hertfordshire Engagement Centre, Everyday Lives in War. Part of this article will appear in the author’s forthcoming Soldiers as workers – class, employment, conflict and the nineteenth century military, (Liverpool University Press).

[1] See Nicholas Mansfield, English Farmworkers and Local Patriotism, 1900-1930 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2001).

[2] Clive Emsley, British Society and the French Wars, 1793-1815 (London: Macmillan, 1979), 133 and 169 and Linda Colley, Britons – Forging the nation 1707-1837 (London: Pimlico, 1991), Chapter 7.

[3] James Dawson Burn, The Autobiography of A Beggar Boy, (London: Tweedie, 1855, [1978]), 64-5. Though long suspected as an ‘urban’ myth, bone grinding is recorded as fact in Neil Oliver, Not Forgotten, (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2005), 42-5 and von Leibig is cited in Edward Russell, The Fertility of the Soil (Cambridge: CUP, 1921), 58.

[4] Nick Mansfield, ‘Grads and Snobs: John Brown, Town and Gown in early nineteenth-century Cambridge’, History Workshop Journal, No. 35, Spring 1993, 183.

[5] H.Cooper, Annals of Cambridge, Vol. IV, (Cambridge: Metcalfe and Palmer, 1852), 483.

Images:

A rare gravestone of a British rank and file soldier of the Napoleonic Wars; Sergeant William Yuill of the Grenadier Guards, 1814.

Fred Mansfield (1912-2004) and Martha Mansfield (1860-1941), c.1936. Martha’s grandmother had celebrated the battle of Trafalgar as a child.

-

What a fascinating article, Nick. I had never thought of such a connection before. I’m sure you’re right that your ancestors would have found a lot of recent events maudlin and sentimental. I suppose a lot of it goes back to Owen and Brook and co.. Who were the poets of that previous conflict? I can only think of Southey, but there must have been more but not I suppose combatants .. Thanks very much

Caro

Submit a Comment

Comments