Articles

One Comment

By Voices

On 14, Jun 2017 | One Comment | In Gender | By Voices

‘Girls Who Would Fight’: Young Women and the Call to Arms

Marcus Morris, MMU

At the outbreak of the First World War, Britain’s army compared to those on the continent was small, with hundreds of thousands of men required to successfully prosecute the war. Hoping to exploit perceived (if debated) ‘war-fever’ in the country a campaign for volunteers was launched.

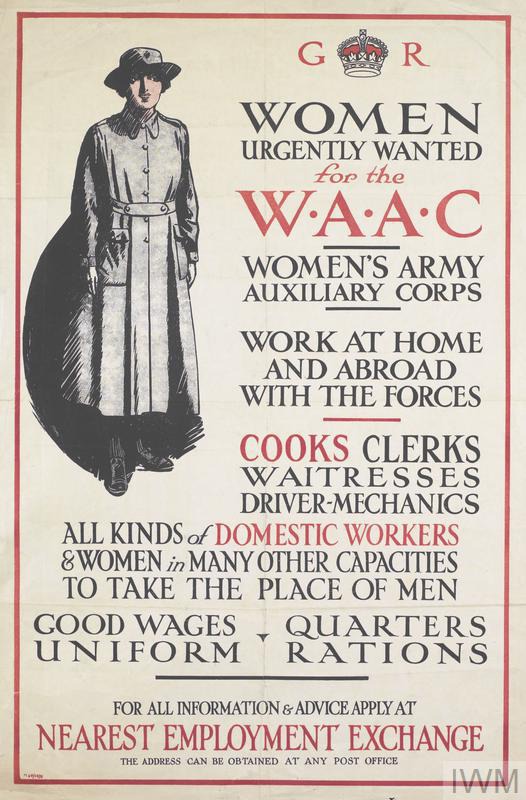

Hundreds of thousands of men would answer the call in the first few months, with a multitude of motivating factors inspiring them to volunteer. Among those were around 250,000 underage recruits over the course of the war, and we have become familiar with the stories of these ‘boy soldiers’. Commemorative activities have centred on their actions at the front and they have been mythologised to some extent. Such stories, though, have centred on the ‘boys’ who wanted to fight. Young women and their responses to the call have largely been ignored, with studies of their roles underpinned by gendered assumptions of passivity, domesticity, duty and nationhood. Yet many young women were as keen as their male counterparts to serve their countries on the front line, and would be continually frustrated in their desire to take up the call to arms.

The contemporary press would tell the stories of many of such ‘girls who would fight’. Though often, it must be said, in an amused or bemused tone. One ‘girl who wants to fight’ contacted her local newspaper, the Yorkshire Telegraph and Star, ‘to ask why we strong and healthy girls may not join the Colours?’ She continued, asserting that ‘I for one, and I’m quite sure there are many, many more, would gladly sacrifice all for their dear King and country’. Given the need for volunteers she questioned, given ‘there are a great number of men, who, I may say, are almost afraid to join, and yet have nothing whatever to hinder them doing so. May we not take their place?’ Other young women would more directly test the resolve of recruiting sergeants. Elsie Mallett (19), for instance, wrote to the secretary of the London Volunteer Rifles stating that ‘I wish to fight in the trenches with all the thousands of brothers that are there. I want to fight for my King and country’. Frances Phillips (20), meanwhile, wrote to her local recruiting officer in Manchester, declaring that ‘she wanted to be a soldier’. For some, simply volunteering their services was not enough. In Blackburn, the Manchester Guardian reported, ‘nearly a hundred girls have established a woman’s defence corps to perfect themselves in shooting, drilling, and ambulance work. Their officers are Bessie, Marian, Annie, and Edith Cowan, four sisters, who are ambitious to fight in the trenches’ and were willing to ‘enter upon serious military training immediately’.

Many of these ‘girls who would fight’ echoed the sentiments of another young Blackburn woman, Gladys Davidson, who, when interviewed by the Manchester Courier, complained that ‘it was very unfair that men alone should be eligible to fight on the battlefield’. Davidson was ‘prepared to make any sacrifice to render assistance to her country at this hour of need’. Like many of their male counterparts, many of these young women were fighting for King and country, inspired by a sense of duty, patriotism and nationhood. Moreover, though not subject to the same pressures as young men, many still felt a sense of shame that they were not fighting. Frances Phillips acknowledged this when she remarked that ‘when I read the paper and see how our boys are fighting I feel a coward staying at home’. For some young women, it was this shame that fuelled their sense of unfairness in not being allowed to fight. For many more, though, the feelings of unfairness had a gendered dimension and were a reaction to those who argued women were unable to fight.

One correspondent to the Yorkshire Telegraph and Star justified women’s presence on the battlefield by arguing that ‘I’m quite certain that we [women] should fight, after a little training, just as well (if not better) that they [men] would, and should simply delight in giving the Germans a “good hiding”’. The ‘girls who would fight’ thus insisted that they had the necessary – if not superior – skills and attributes necessary to be a good soldier. Gladys Davidson highlighted her shooting capabilities, boasting that she ‘has secured many trophies in shooting competitions in various Lancashire contests’. Frances Phillips, meanwhile, focused on her physical capabilities, telling one particular anecdote to outline her potential: ‘Lots of people have told me I have plenty of strength, and I have had to use it on occasions to defend myself. A year or two ago I was coming home from a dance … when a big man stopped me and tried to snatch my bag. I gave him one “lander” in the face and knocked him down’. Nevertheless, despite attempting to minimise gender differences, both these young women felt the need to masculate themselves by offering to cut their hair. Davidson stating that she ‘would be quite willing to part with her locks of auburn hair if this would assist her to achieve her ambition’.

Such gendered assumptions permeated the responses to those young women who expressed a desire to fight on the front line. In the contemporary press, there was little support. The support that was offered seemed to stem from belief that this would stir men into action. One male correspondent claiming that ‘if some of the girls got into khaki it would shame some the fellows who had never tried to join and didn’t want to’. The recruiting sergeants instead suggested that ‘girls who want to fight’ should look to nursing if they wanted to contribute to the war effort. The majority of criticism, though, seemed to come from female voices. One argued that ‘such talk is ridiculous for females to fight against such brutes as the Germans’ and directly countering the desire to give them ‘a good hiding’ that ‘it is a very weak man who lets a woman give him a good hiding’. Another, meanwhile, countered the arguments that women were equal to men by stating that ‘I am quite confident women can do most things equally with men, but I draw the line at killing’. She went further, contending that ‘those apparently thoughtless girls’ should not be ‘envying our brave Tommies’.

Many young women, though, did envy their male counterparts who could fight, just as many of the underage ‘boy soldiers’ envied older men. Young women often envied the ‘brave Tommies’ for the same reasons that young men did: they felt bound by duty and patriotism to defend their nation in its hour of need, they were influenced by societal pressures that came with the call to arms, and, of course, there was glory to be earned. Yet, for young women, there was further motivation in that it was their sex that precluded them going to the front. Society conditioned by gendered assumptions of passivity, domesticity, duty and nationhood had decided that ‘girls who would fight’ were neither capable of doing so nor should be allowed to do so. Yet, as Frances Phillips pleaded: ‘surely I have got hands and strength to help to fight for my country … if you would only give me a chance’.

Marcus Morris is currently working on a Voices community fund project, ‘Being Young on the Home Front’, more information available here.

-

ROOTS

We wanted to fight and be on the front line

But of course they didn’t let us, after all we are just women.

All we are good for is housework and domesticity

But of course all those assumptions are wrong

We are not just women.

We are strong.

Stronger than any men fighting on the front line

While they are fighting we are saving society

Without us our country would be non-existent

We are the backbone of England.

We can do much more that what the men say we can

After all, men have never understood women

And they never will.

WE ARE ENGLAND.

We wanted to fight and be on the front line.

Submit a Comment

Comments