Articles

No Comments

By Voices

On 03, Aug 2015 | No Comments | In Belief | By Voices

Glasgow University’s Great War: Chaplains and Theology Students

Alicia Henneberry, postgraduate student

Theology and Religious Studies, University of Glasgow

The Glasgow University Great War Project is remembering the many men who fought and died bravely on the front lines in World War I. For this particular facet of the project, I focused on an aspect of this war that took place much closer to home for those of us on the University of Glasgow campus. I endeavoured to uncover aspects of the lives of those who studied and served from the University of Glasgow’s Divinity Faculty – the Chaplains and Theology Students of World War I.

Still a major part of the British Armed forces, military chaplains are ordained members of various denominations, including the churches of Scotland and England, who hold commission in the army, ministering to soldiers in times of war and peace. Though the University Archives’ theology and religious studies collection does not contain information of the war services of these men specifically, they have illuminated their educational background. This project was a unique opportunity to delve into the lives of these men before they went to the front, and study how the war affected religious belief and education.

The collection itself is comprised of several items, three of which I will be featuring that I feel were the most telling of the education and life at the Faculty of Divinity during World War I.

Preachers before the University

![Register of the Preachers before the University [University of Glasgow Archives: CH 2/1]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/uog-archives-ch21-460x310.jpg) The particular item that I will focus on first is the “Register of the Preachers before the University” (CH 2/1). As the name suggests, this is a logbook listing the names of all those who gave sermons or lectures to Divinity students during the first half of the twentieth century. Along with the names is included the date upon which the sermon was given, the title of the sermon, and the relevant Bible verses that the speaker referenced. At first glance, this source seems particularly straightforward and simple, listing no more than names and titles with no specific mention to the war raging to the south. However, once I looked closely at the titles, Bible texts and verses, as well as the dates and who was speaking, I was able to gain a lot more information.

The particular item that I will focus on first is the “Register of the Preachers before the University” (CH 2/1). As the name suggests, this is a logbook listing the names of all those who gave sermons or lectures to Divinity students during the first half of the twentieth century. Along with the names is included the date upon which the sermon was given, the title of the sermon, and the relevant Bible verses that the speaker referenced. At first glance, this source seems particularly straightforward and simple, listing no more than names and titles with no specific mention to the war raging to the south. However, once I looked closely at the titles, Bible texts and verses, as well as the dates and who was speaking, I was able to gain a lot more information.

![1 November 1914: The Duty of Courage [University of Glasgow Archives: CH2/1]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/uog-the-duty-of-courage-460x310.jpg) Generally, these sermons appeared to be nothing out of the ordinary of a divinity lecture, with titles such as “Commentary on the Romans” and the “Gospel of St. Mark.” However, once we look past August 1914, when Great Britain declared war on Germany, we can detect from the titles alone a marked increase in themes that are undeniably war-related. Given by a variety of speakers, the sermon titles all allude to themes such as courage and duty, as well as morality and steadfastness. One example was given on November 1st, 1914 by Haller Mursell, the Minister of the Coats Memorial Church of Paisley at the time, who spoke on the “Duty of Courage” quoting Joshua 1:5, a verse which speaks on the unwavering strength of God. These themes become only more pronounced once looking at those sermons given towards the end of the war. Dr. HMB Reid, one of the Professors of Divinity and one-time Dean of the Faculty, gave many in this theme, such as “The Bad Dream of War” on Oct. 19 1919. The chaplain to the Clyde Defences, W.W. Beveridge, appears to have given a similar lecture February 3rd 1918, entitled “The Spirit of our Fighting Men.” The Bishop of Durham even came to address the Glasgow Divinity men, speaking on what was most likely the aftermath of the war in a sermon entitled “Christian Duty in Difficult Times” on October 24th 1920.

Generally, these sermons appeared to be nothing out of the ordinary of a divinity lecture, with titles such as “Commentary on the Romans” and the “Gospel of St. Mark.” However, once we look past August 1914, when Great Britain declared war on Germany, we can detect from the titles alone a marked increase in themes that are undeniably war-related. Given by a variety of speakers, the sermon titles all allude to themes such as courage and duty, as well as morality and steadfastness. One example was given on November 1st, 1914 by Haller Mursell, the Minister of the Coats Memorial Church of Paisley at the time, who spoke on the “Duty of Courage” quoting Joshua 1:5, a verse which speaks on the unwavering strength of God. These themes become only more pronounced once looking at those sermons given towards the end of the war. Dr. HMB Reid, one of the Professors of Divinity and one-time Dean of the Faculty, gave many in this theme, such as “The Bad Dream of War” on Oct. 19 1919. The chaplain to the Clyde Defences, W.W. Beveridge, appears to have given a similar lecture February 3rd 1918, entitled “The Spirit of our Fighting Men.” The Bishop of Durham even came to address the Glasgow Divinity men, speaking on what was most likely the aftermath of the war in a sermon entitled “Christian Duty in Difficult Times” on October 24th 1920.

A prominent topic of the sermons during the wartime was the Book of Revelation, the last book of the Bible that infamously speaks of the end of the world and the rewards and punishments awaiting the good and the wicked. Though obviously this section of the Bible could be and is discussed at many different periods of time, not just in war, Revelation is a theme that is largely alluded to in times of crisis and death, and is a theme that again crops up in the last of the sources I will be covering in the third post. There were many sermons to the Faculty, which, towards the end of the war, alluded to Revelation. “The souls under the altar” was one such sermon, which is a reference to Revelation 6:9 that described the murdered, innocent souls rising to be in the Kingdom of God; an image that could be applicable to the thousands of dead boys and men on all sides of the conflict.

Even though there is no actual recording of these sermons to be found in this ledger, and we are left with only the title and Bible verse alluded to by each speaker, it is clear from many of these titles that the war was prominent in the minds of these men and important to Divinity in order for so many of the talks to be focused on it.

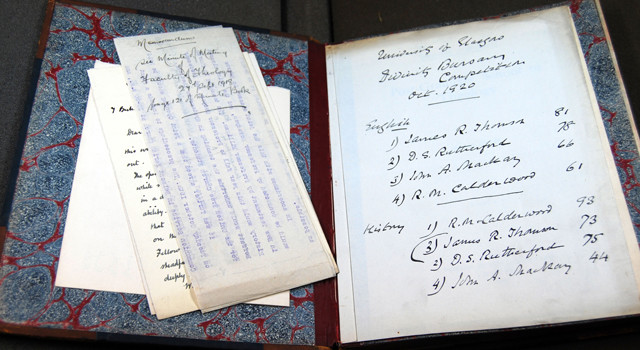

Meeting Minutes of the Divinity Faculty During WWI

![Faculty of Divinity minute book [University of Glasgow Archives: DIV1/4]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/uog-faculty-of-divinity-minute-book-460x310.jpg) The meeting minutes for the professors of Divinity give a good idea of how the war affected the department over the duration of the war. The University Archive is in possession of two minute books for the war years, Glasgow University Archive References DIV1/4 and DIV1/5, which cover the meetings that took place in the first half of the twentieth century. (For anyone interested in perusing these records for themselves, I would highly suggest looking at DIV1/5, as the handwriting is much more legible!)

The meeting minutes for the professors of Divinity give a good idea of how the war affected the department over the duration of the war. The University Archive is in possession of two minute books for the war years, Glasgow University Archive References DIV1/4 and DIV1/5, which cover the meetings that took place in the first half of the twentieth century. (For anyone interested in perusing these records for themselves, I would highly suggest looking at DIV1/5, as the handwriting is much more legible!)

Much like the sermon logbook, the meeting minutes contain largely formal and quantitative information about the day-to-day business of the Divinity Faculty. Each entry begins by naming the Dean and Professors present, as well as who was recording the minutes that session. Many of the entries contain discussion of courses, letters and requests received by the Dean, General Assembly of the Church of Scotland news, and other tidings. However, bits and pieces of the war are scattered about, culminating sadly by the end of the conflict, where I was able to see just how devastating the war was to the Divinity Faculty.

The first mention of the war occurs in the month of February 1915, six months after Britain declared war on Germany. In these entries, the Dean of the Faculty, Dr. Cooper, lists several names of the students who had left for military service. A letter was also read from the General Assembly, which discusses measures to be taken in regards to the interrupted studies of those who had left. The entries conclude with the Faculty saying that the theological students would be provided with guidance by those assembled, and their education would be looked after. A year later, in the entry dated February 16, 1916, special allowances were being made for students on war service:

“[I]t was unanimously agreed to the meet the case of Divinity Students who had served in the army in the present War. The Faculty recommend that a Theological course of two regular session should be accepted instead of the normal course of three sessions. A qualifying summer term of three months duration should be instituted and count in the reckoning of a student’s course.”

There were many students who interrupted their education in order to serve in His Majesty’s Forces, as we can see from the clear and very helpful list provided on page 70 of the meeting minutes, which names all of those students who were in the middle of their studies and left, as well as those who had to postpone starting their degrees. This list provides the names of the Divinity students who enlisted, as well as their years, degrees, and the regiments they joined. In total, a large group numbering over forty students who had already enrolled left for the front, with numerous potential students joining them.

The high number of students on service took a great toll on the department, as I saw reading on. As of 1917, the minutes revealed that the Divinity Faculty of Glasgow University negotiated a merger with the Theological College of the United Free Church. On page 79, dated March 3rd 1917, the minutes record:

“…it was unanimously agreed that the whole question of co-operation between the United Faculties of Divinity and the Theological Colleges of the United Free Church during the period of war should be discussed at a conference on the opening day of the assembly.”

It was later decided that joint classes would be held between both colleges. Such a merger suggests that each institution had lost a large number of not only students, but also lecturers and staff. One such lecturer from the Divinity Faculty who departed for war duty was Dr. Stevenson, who had left for service in London.

Not only was the attendance of students dramatically affected by the war, but also the resources and money available to the pupils who were left. Discussed in the meeting minutes at various points over the wars years were letters from individuals wishing to apply for teaching posts at the Divinity Faculty. One such letter from Mr. Charles B. Marbon was read on the 21st of February 1917. He wished to be taken on as a teacher of Elocution. However, as with several other petitioners, the Dean and Faculty decided that it was “inadvisable” to add to the list during the “duration of the War.” The scholarships and funding readily awarded to students before the war, such as the prestigious Black Fellowship, also had to be suspended under the Emergency Powers Act enacted by the British government in 1915. On February 4th, 1918, the meeting minutes reflect this financial hardship, as the entry reads:

“The Faculty took into consideration the remit from the Senate to consider in connection with the Emergency Powers Act 1915 what prizes, Bursaries, or other Emoluments should be recommended to the University Court for suspension during the years 1917-1918 and 1918-1919, in view of the absence of candidates on war service…after consideration the Faculty decided to recommend for suspension in accordance with the above, the Black Theological Fellowship, the Jamieson Prize and the Thindlater Scholarship Prize.”

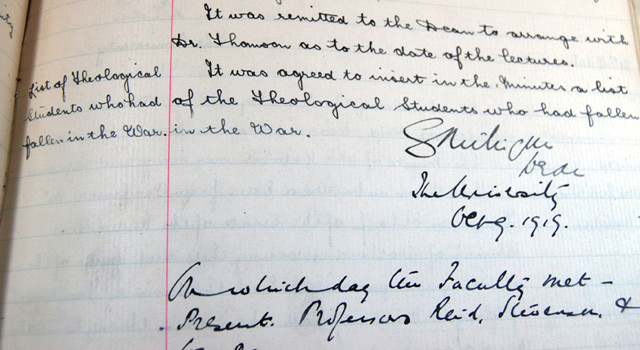

![Minute to list Theology students who died in the war [University of Glasgow Archives: DIV1/4]](http://www.voicesofwarandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/uog-theology-students-who-died-in-war-460x310.jpg) We can clearly tell from the meeting minutes and brief mentions of the war that it had a dramatic impact on Divinity at Glasgow. The Faculty slowly lost many students, forced to join forces with outside institutions to make up for these losses, and could no longer support additional staff or scholarships for the remaining candidates. We can surmise through these meeting minutes that these professors truly cared for their students at war and for their education. One such example was seen in the entry for September 24, 1918, when the Faculty stated that they wished to write to Professor Medley (Professor of History and head of the Military Education Committee), who was stationed with the YMCA in France, to “keep in view of the need of theological students on active service.”

We can clearly tell from the meeting minutes and brief mentions of the war that it had a dramatic impact on Divinity at Glasgow. The Faculty slowly lost many students, forced to join forces with outside institutions to make up for these losses, and could no longer support additional staff or scholarships for the remaining candidates. We can surmise through these meeting minutes that these professors truly cared for their students at war and for their education. One such example was seen in the entry for September 24, 1918, when the Faculty stated that they wished to write to Professor Medley (Professor of History and head of the Military Education Committee), who was stationed with the YMCA in France, to “keep in view of the need of theological students on active service.”

This source enlightened me greatly on just how devastating the war was to the resources and number of students in the department, and gave hints of the remorse and stress the Faculty must have been feeling at the time. As a theology student myself, reading these minutes gave me a sobering moment. An entry on October 20th, 1915, a letter from a very bright student named Robert Stevenson was read. He asked if he could suspend his Black Fellowship prize, as he was going off to war, but would still like to be funded when he returned. The Faculty approved this with no question, yet Robert Stevenson’s name can be seen on the list of those students who were killed in action, never to be able to return home to his studies.

Theology After the War

What was the legacy of the First World War in post-war theological thought? I now will focus on an item in Glasgow University Library’s Special Collections entitled Theology After the War. This lecture given by Professor HMB Reid at the closing of the 1915-1916 school year to the Divinity Faculty confirmed many of my archival findings about the general temperament of the Faculty during the war, and reveals just how much of a toll the war took on the hearts and minds of these lecturers and their students.

As we have seen from the meeting minutes and lists in the University Archive, dozens of students left for the front, leaving behind their textbooks in favour of weapons and uniforms. The opening of Professor Reid’s lecture illuminates just how big of an impact the war made:

“We have watched the steady ebbing of our numbers, and to-day we are face to face with the fact that practically all our students have been armed for the national service. Nearly fifty of them are either in home cantonments getting ready, or in the field of battle.”

For the Divinity Faculty, forty students was a substantial level of participation.

We know from meeting minutes and a sermon book that the Faculty was concerned for the students and their education, and that the war was always on their minds, but this sermon clearly illustrates not only their remorse in the loss of so many of these student’s lives, but how proud and honoured they were to be their colleagues:

“Men speculated idly, how the theologians would behave. The result surprised all but those who live among our divinity men, and know their mettle. First in ones and twos, then in blocks, our best and our second best heard the call…Our men have proved their manhood. They have shown that the Divinity Hall is no refuge for slackers or detrimentals, but proportionally the most martial section of the University.”

It is a stirring and emotional lament that illustrates the patriotism and bravery of the men from Divinity, and how much pride the Faculty had for its pupils. It continues:

“The strain has not been slight. There has been real sacrifice and pain; but never has one of the finally made his choice for God and country without feeling a wonderful sense of joy. I have seen those happy, exalted looks of men who came to say—“I have attested”—or I am ordered on service.” Some of us saw the light on Robert Rennie’s face as he came up the worn stair in his new uniform, promoted from the ranks, to tell us that he was a subaltern in his old regiment, and “going out again” to France. A few weeks after, he fell. His death will preach even better sermons than he would have written had he lived. It has preached already to us in this Hall in many an hour, and with it have been mingled the voices of Monteith, Fenwick, Gordon Macdonald (most gallant soldier of Christ!) Forsyth, Macfarlan, Macgregor, Herbert Dunn, and others of our band.”

The sermon also enlightened me on how the education of theologians changed after the war. As I mentioned in my second post, Faculty meeting minutes detailed the types of classes taken by students over the years, but I had not yet been able to surmise how the war impacted theological thought at the Divinity Faculty. Thankfully, as the title of Professor Reid’s sermon suggests, this particular source provided a wealth of information on the change in education. Towards the end of the sermon, he invites his audience to question, “What of Scottish Theology after the War?” He discusses many terms familiar to a student of theology today, mentioning the influence of Schleiermacher (in Reid’s view, negative), denouncing Ritschlianism, and asserting the need for a post-war rise in Scottish systematic theology, believing that they have been too dependent on developments in German and American thought.

Reid ends the lecture passionately, lamenting the war and the students they had lost, but believed that the courage of their students would only fuel a resurgence of theological study:

“…[T]he wave of human faith and experience rolling into our classroom will give the impulse and force required. Who can ever again study the Christian ultimate with detachment, who had learned what God and Christ and Holy Spirit, what Man and Sin and Atonement, and the eternal fellowship of the Church, means for fighting and suffering souls? It needed but this tragic upheaval to throw up the Verities of the Faith into bold and arresting belief.”

He asserts that as a Faculty, they will use this remorse and memory of their fine students to get back to the “essence of religion” which is the “truth of the incarnation.” He moves to return to an emphasis on the supernatural, moving away from the “remolded basis of theology after Schleiermacher” to once again play “the Church’s winning card.” He wished to study the Living Christ through apologetic theology, an image that had been brought back into focus with such a heavy amount of wounded and dying men. It is the figure of the resurrected Jesus Christ and “martyr’s graves” that is very prevalent in this lecture, harking back to many of the Revelation lectures I pointed out in the sermon log book. It is with this vision that Dr. Reid concludes, declaring that they shall set about the task of reviving Scottish theology, which had been enriched “with the blood and sacrifice of our best and most scholarly Scotsman.”

When beginning this project, Glasgow University’s Great War Project did not know what to expect. Would we learn anything about the war through the eyes of this department? Was theological education at the University of Glasgow affected by the war at all? Would the war even be mentioned? What I have found has been beyond my expectations of the project. Not only was it very clear how much the war impacted the resources and numbers of the Divinity Faculty, but I also encountered a very moving and tragic story of a brave and patriotic group of students and their proud professors, all of whom were deeply affected by the death and bloodshed, yet were resilient in their endeavours to study religion and theology. Not only did Dr. Reid’s sermon show how determined the divinity men were to carry on educating despite the loss of almost their entire student body, but also how profound an impact the Glasgow-trained chaplains and others like them brought to the front. Dr. Reid stated in the sermon how “strangely” welcome his students were to the other soldiers, and how these soldiers sought out the company of these ministers for advice and comfort in such dreadful times. Indeed, sources on army chaplains in the Great War suggest that though belief in organised religion was remiss among the troops and would substantially decrease in post-war Europe, chaplains and ministers -university students and graduates- became well respected and liked by the masses, and in turn were inspired by the “unconscious Christianity qualities” and steadfastness of the soldiers.

This collection is quite fascinating for any of those interested in a historiography of theological study, as well as how the war affected those on the home front and in higher education. Though I only highlighted a few of the sources that I thought provided the most information on the impact of the war on Divinity at the University of Glasgow, the University Archive and Special Collections house many fascinating materials, including pamphlets for the different degrees offered, correspondence to other universities, and class lists. And if you ever find yourself in Number 4 the Square, the Theology and Religious Studies’ current home, take a look at a rather faded set of photographs hanging on the first-floor landing. You will come face-to-face with the black and white portraits of twenty-two young men in both uniform and suits. An inscription in Latin declares that these faces are the heroes of Dr. Reid’s sermon and of University of Glasgow Theology, who died for their country in time of war. These are the men who left their studies to defend the United Kingdom, taking the education they received at the University of Glasgow to the front, bringing comfort to their fellow soldiers and inspiring their colleagues at home to carry on.

This collection is quite fascinating for any of those interested in a historiography of theological study, as well as how the war affected those on the home front and in higher education. Though I only highlighted a few of the sources that I thought provided the most information on the impact of the war on Divinity at the University of Glasgow, the University Archive and Special Collections house many fascinating materials, including pamphlets for the different degrees offered, correspondence to other universities, and class lists. And if you ever find yourself in Number 4 the Square, the Theology and Religious Studies’ current home, take a look at a rather faded set of photographs hanging on the first-floor landing. You will come face-to-face with the black and white portraits of twenty-two young men in both uniform and suits. An inscription in Latin declares that these faces are the heroes of Dr. Reid’s sermon and of University of Glasgow Theology, who died for their country in time of war. These are the men who left their studies to defend the United Kingdom, taking the education they received at the University of Glasgow to the front, bringing comfort to their fellow soldiers and inspiring their colleagues at home to carry on.

Sources:

Records of the University of Glasgow Faculty of Divinity, University of Glasgow Archives References: CH2/1, DIV1/4 and DIV1/5

Royal Army Chaplains’ Department http://www.army.mod.uk/chaplains/chaplains.aspx

Edward Madigan. Faith under Fire: Anglican Army Chaplains and the Great War. [Palgrave School Print, 1 Mar. 2011]

Further Reading:

- John Dunlop. Preaching the gospel in the midst of conflict. [Belfast: Rosemary Presbyterian Church, 1987]

- Andrew Todd. Military chaplaincy in contention: chaplains, churches, and the morality of conflict [Ashgate Publishing Co, May 28, 2013]

- Traditions of Theology in Glasgow, 1450-1990, W. Ian P Hazlett Edinburgh 1993

- On the theology of Friedrich Schleiermacher: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/schleiermacher/

- On Ritschlianism: https://archive.org/details/ritschliantheol00garv

- On the Book of Revelation and war imagery: Elaine H. Pagels. Visions, Prophecy, and Politics in the Book of Revelation.

Submit a Comment